DATS 50th Anniversary Conference

This September the Dress and Textile Specialists network (DATS) are holding their 50th anniversary conference: “Shaping Culture through Dress and Textiles”. I submitted an abstract and was asked to submit a poster, which will be distributed with the proceedings pack PDF and displayed in print at the conference venue. With only an A4 sheet to work with, I created a poster that prioritised visuals, and invited conference goers to scan a QR code to view the full gallery of images and my analysis. If that is how you managed to find this write-up, then welcome!

ℹ️ This journal entry is not intended as publishable academic research, but as a record of the primary source evidence underpinning the conference poster and its claims. For clarity, readers unfamiliar with Marian Clayden or the Foundation should note that the subject is referred to as ‘Marian’, reflecting both the author’s personal familiarity and to avoid confusion with the author sharing the surname.

Documented Dialogue

Marian Clayden’s Archival Attributions to Gujarati Design

In 2003, Marian Clayden travelled to Ahmedabad, India and photographed her participation in a dye workshop led by local artisans. Once back in the United States, she processed the photos into film slides and in following years used the techniques from the workshop to design garments for her 2004 and 2005 fashion collections. Afterwards Marian organised the workshop slides into an archival box labelled “Ahmedabad” and interpolated slides from her 2004/05 collections amongst the workshop images to assert the continuity between Gujarati workshop practices and her own designs. This case study calls for a re-examination both of Marian’s works held in museums and contemporary debates on transnational cultural exchange. By foregrounding an archivally significant example of the translation of traditional craft techniques into Western fashion, it complicates concepts of heritage and authorship in Western fashion systems.

By 2003, Marian had cultivated a reputation as a creator of luxurious textiles inspired by a variety of global cultures. Originally a textile artist creating wall hangings and fibre sculptures, Marian established her artistic reputation in the 1960s and 1970s, using resist-dyeing techniques and terminology originating in both Asia and Oceania. (Larsen and Hanson, 1976, p.234) She later transitioned into commercial fashion in 1981, designing collections of garments to be sold through America’s most elite department stores: Bergdorf Goodman, Saks Fifth Avenue, Neiman Marcus. During this time, her use of global textile and costume practices remained a cornerstone of her creative process.

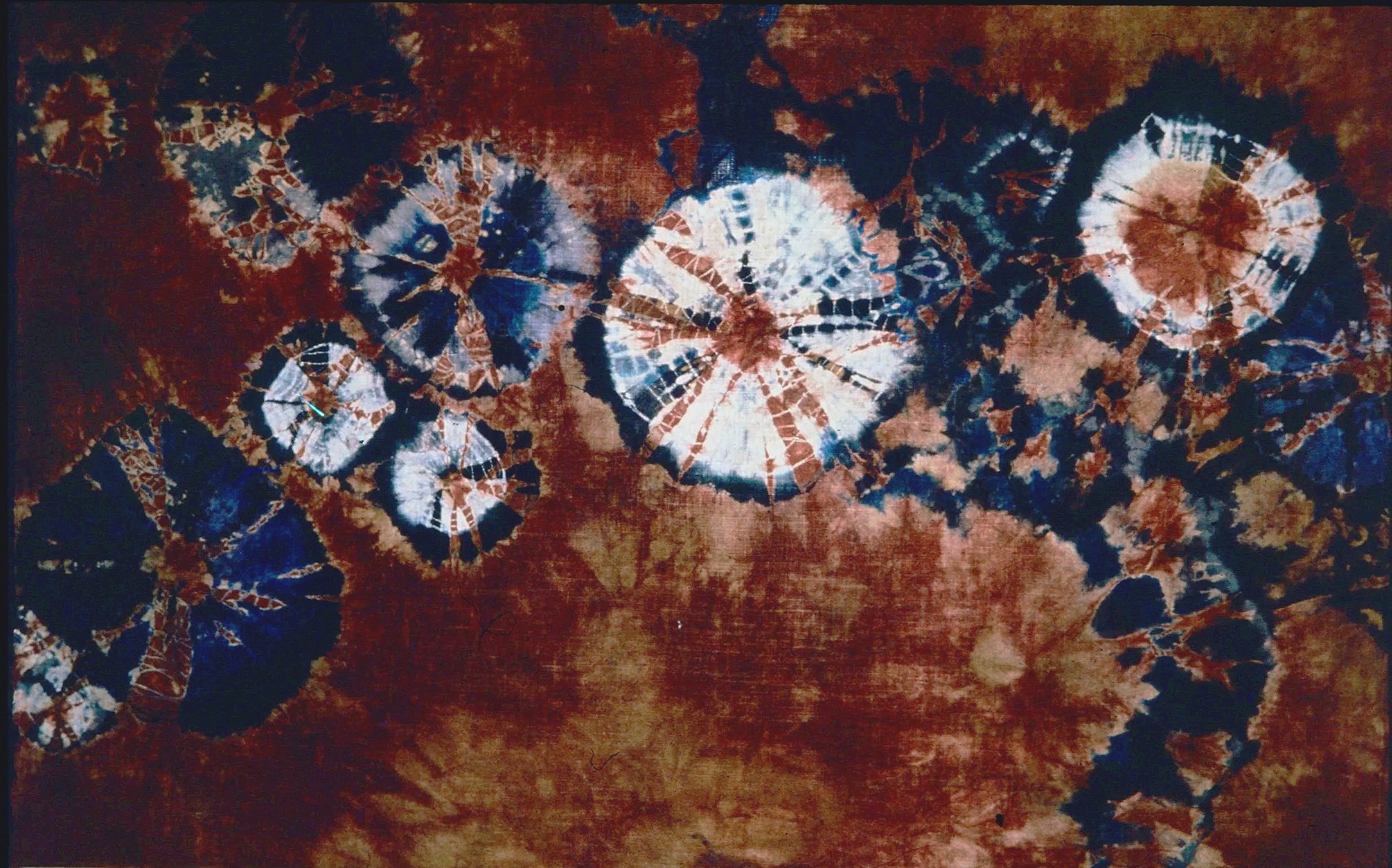

Figure 1: Australian Stone Country, 1968

Marian Clayden (1937-2015)

While not related to the Ahmedabad workshop, this early Clayden demonstrated Marian’s dyeing techniques and incorporation of inspiration derived from time spent abroad (in this case, in Australia) as part of her process.

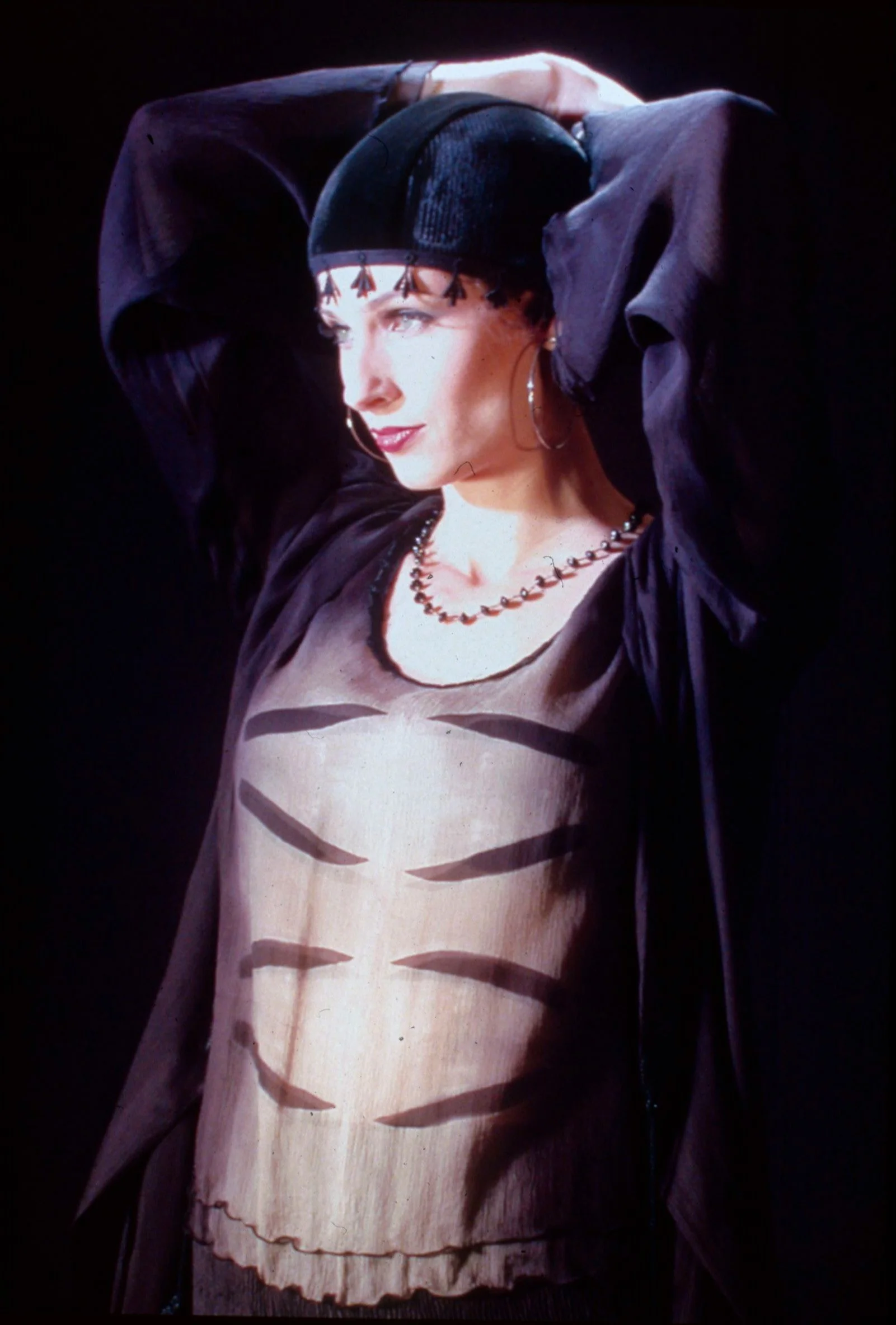

Figure 2: Water Lily Ensemble, F/W 1999

This ensemble, from New York Fashion Week, uses Marian’s ‘Water Lily’ fabric. The design motif of the water lily is associated with Iran, among other cultures. Marian lived in Iran for a short time in the 1970s.

Marian’s significance as a textile artist earned her a place in the collections of several major institutions including The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Victoria and Albert Museum, and the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. Marian’s close, personal relationship with Milton Sonday, Director of the Cooper-Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum, resulted in the current substantial collection of her textiles within their collections. The objects contained within these cultural institutions demonstrate Marian’s influence in the fields of textile design and fashion, and her use of global textile traditions in their creation evidences her interactions with the design practices of Iran, Japan, and India. This analysis focusses on the latter.

Archival Images

As the significance of these findings are both archival and photographic, the following section presents the most relevant photos below with supporting text to describe their significance. These photos are presented in Marian’s original order, preserved in the archival slide boxes she compiled in the mid-2000s.

Archival Slides, in order

Figure 3: This image shows local women teaching and practicing traditional bandhani techniques, establishing both the site and artisanal context of Marian’s later interpretations. This slide anchors the provenance of Marian’s designs both in place and time: at this Ahmedabad dyeing workshop.

Figure 4: A close-up image of Artisan Blouse from Marian’s Fall 2004 catalogue. Its designs reproduce the techniques visible in later workshop images.

This photo is dated after the Ahmedabad slides, establishing a direct archival bridge between the workshop’s practices and Marian’s garments.

Figure 5: This image illustrates both the clamp-resist technique and the workshop’s social dynamics, juxtaposing older figures in traditional dress with younger participants in Western clothing. Marian’s inclusion of this image evidences her intent to document the workshop as a place of cultural preservation, which she subsequently echoed and reinterpreted in her fashion practice.

Figure 6: This image depicts detail of bound-resist techniques on a dark blue fabric. Marian’s use of these techniques on the shoulders, cuffs, and collar of Artisan Blouse (Figure 4) means this photo is evidence of the direct source of a technique translated into her commercial garments.

Figure 7: This detail shows a fine stitch-resist technique with contrasting streaks, echoed both in Float Dress (Figure 10) and Shadow Camisole (Figure 11). These visual similarities reinforce Marian’s archival claims of this Ahmedabad workshop being the inspiration for her fashion collections.

Figure 8: Detail of pre-dyed fabric being embellished. These square motifs are also seen on Artisan Blouse (Figure 4) and create the direct link between this workshop and Marian’s garments in major department stores.

Figure 9: Detail of striped cloth, with a pattern identical to that seen on the scarf accompanying Artisan Blouse (Figure 12).

Figure 10: A Marian Clayden model poses in a photoshoot wearing Float Dress from the Fall 2004 collection. Marian’s self-attribution of these artisanal influences in Western fashion requires curators to reassess concepts of provenance and cultural exchange in early twenty-first-century fashion.

Supplementary images, not included in slides

Figure 11: Shadow Camisole, Fall 2003

This image, not included in the original slides, has obvious visual similarity to the techniques seen in Figure 10.

Figure 12: Artisan Blouse and scarf, Fall 2004

The blouse here from Figure 4 is shown in a commercial shoot, with the bandhani techniques evident on the collar and shoulder. In the lower right, a red, white, and black striped scarf matches the techniques from Figure 9, completing the transfer from dye workshop to fashion photoshoot.

Curatorial Implications

Marian’s most recent exhibition was her 2016 retrospective, shown in multiple museums throughout the UK. While Marian died prior to the first exhibition at the Harris Museum in Preston, she had already selected all of the objects for the show. Mary Schoeser, experienced curator and personal friend of Marian, staged the exhibition and provided the copy for the gallery guide and displays.

One section of the exhibition was named “Global Sensibilities” and briefly discussed Marian’s interactions with international cultural practices, saying: “Having lived in four countries and travelled around the world, Clayden’s trail-blazing textiles embody a global sensibility. She drew inspiration from Kabuki, opera and modern dance, from many countries’ garments and cloths, but also from her acute observations of nature...” (Fashion and Textile Museum, 2016) While the exhibition did draw a direct link between Marian’s participation in Hungarian folk workshops and the way they inspired felt garments displayed in the exhibition, no other mention of design translation was referenced.

Marian’s attribution of her felt work to her participation in the Aid for Artisans workshops in Hungary are better documented, both contemporaneously and retrospectively. Marian’s archive also provides evidence of her participation in these Hungarian workshops, but without the interpolation of finished Clayden garments. Considering both Indian and Hungarian workshops together reveals Marian’s pattern of participating in charitable artistic endeavours with Aid to Artisans and interpreting her experience through her artistic practice: designing fashion garments. This approach is absent from commentary supporting her retrospective exhibition and from the recent Textiles: The Art of Mankind exhibition at the Fashion and Textile Museum curated by Schoeser, which included one of Marian’s Hungarian hats. (Fashion and Textile Museum, 2025)

When asked, Schoeser confirmed that she was unaware of these slides when staging the exhibition. Were Marian’s retrospective exhibition to be restaged, the archival discovery of the Ahmedabad workshop and attributions offers curators the opportunity to reinterpret Float Dress as a product of those workshops and place it in the “Global Sensibilities” portion of the exhibition as a parallel to the Hungarian pieces. Both demonstrate Clayden’s commitment to hands-on learning with local artisans, and both are linked to Aid for Artisans as a vehicle for that learning. Reframing Float Dress in this way would strengthen the assertion of Marian’s “Global Sensibilities” and enable a contemporary reassessment of late twentieth- and early twenty-first-century debates on cultural exchange and appropriation.

These findings also reframe two other recent exhibitions. The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco’s recent Fashioning San Francisco exhibition included a section focussed on increasing globalisation and its effects on the designs seen in San Francisco. The exhibition gives several examples of cultural appropriation, including Yves Saint Laurent’s Bambara dresses in 1967: beadwork dresses inspired by the Bambara people of Mali with no active engagement with the Bambara community. (Camerlengo et al., 2024, p. 195) Marian’s archive attests to her work with Gujarati workshop leaders, but does not evidence sustained engagement with the Ahmedabad community, and the only attribution of this collaboration is found within her private materials. Here Marian’s work was more transparent than earlier extractive processes, but falls short of the contemporary understanding of appropriate cultural exchange with source communities. While her attributions do not meet modern expectations, they were innovative at the time, and her efforts to show the design source of her work using accurate names for technique indicate a deliberate engagement with the cultures she drew inspiration from (Figure 13).

The Museum at FIT’s Reinvention & Restlessness: Fashion in the Nineties discussion on the “global wardrobe” would also have benefitted from these findings. That exhibition’s curators used Galliano’s use of Navajo/Diné imagery in 1996-1998 as examples of practices that would be unacceptable today for their lack of engagement with the source of the design, and apparent lack of respect for cultural practices and taboos. The exhibition also mentions China and India as production powerhouses for textiles in the period but does not provide any material examples of Indian practice or exchange. (Hill et al., 2021, pp.142–143) Marian’s work provides a counterpoint to Galliano’s, highlighting engagement with source communities and sensitivity in making by a contemporary designer, and provided an archivally significant example of Indian engagement to augment the exhibition’s existing arguments.

Cultural Borrowing, or Cultural Appropriation?

Despite her passion for travel and the integration of international cultural practices into her work, Marian did not attribute the workshop organisers or tutors by name, an omission which repeats patterns of cultural extraction employed by other designers anonymising their sources of inspiration. However, the individuals depicted participating in the workshop and Marian’s interpolation of fashion photos evidences a conscious effort to credit those who inspired her art. Analysing Marian’s position within broader debates on cultural exchange and appropriation is central to understanding the impact of her work and its curatorial implications. However, a fuller analysis of these questions is beyond the scope of this conference poster and will be developed in forthcoming research.

Figure 13: Kantha Coat, Spring 1992

Marian Clayden (1937 - 2015)

Kantha is the term for a form of embroidery practiced in the eastern India and Bangladesh. It is a diverse practice ranging from blankets of varying complexity and intricacy to worn garments like saris.

In 1992, Marian used both the term and the fabric in her Spring collection, directly attributing the foreign design culture in her work.

After her retirement, Marian engaged with the records of both the inputs and outputs of her travels and design inspiration drawn therefrom. In doing so, Marian chose to group the images offered above in order to cite the sources of her work, drawing a direct and demonstrable link between the dye workshops of Ahmedabad and Western fashion’s most elite spaces. Since 2010, fashion makers have become increasingly sensitive to postcolonial narratives and power imbalances. Marian’s attributions thereby sit at a crossroads in practice: more transparent than contemporaries but falling short of what modern scholars identify as equitable relationships between artisans and designers. (Brown and Vacca, 2022)

Conclusions

The discovery of Marian’s personal attribution of her 2004/5 collection to an Ahmedabad dyeing workshop is a significant case study in the conscious documentation and reinterpretation of artisan practice within Western fashion at the turn of the twenty-first century. Beyond reshaping scholars’ understanding of Clayden’s own work, this material offers curators with new possibilities for reassessing provenance and cultural exchange in contemporary art and fashion collections more broadly.

Further research will clarify the implications of Marian’s methods and their divergence from or alignment to trend during her active period, but what remains is a framework to complicate discussions of how Western makers of art and fashion engaged with ethnic sources. Marian’s attribution, although partial, sharpens wider debates on authorship and heritage, questions ethical engagement in museum practice, and demonstrates the value of artist archives in reshaping the modern understanding of cultural exchange in fashion.

References

Bullis, D. (ed.). 1987. Marian Clayden In: California Fashion Designers: Art and Style. Layton, Utah: Peregrine Smith Books, pp.37–40.

Camerlengo, L.L., D’Alessandro, J., Cheang, S., and Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco (eds). 2024. Fashioning San Francisco: a century of style. San Francisco: Cameron & Company.

Constantine, M. and Larsen, J.L. (eds). 1985. The art fabric: mainstream 1. ed. Tokyo: Kodansha International.

Dyer, C. 1980. Marian Clayden: Dyed, Discharged, Dipped, and Dared. American Craft. 40(4), pp.32–35.

Fashion & Textile Museum (2016) Art Textiles: Marian Clayden [Exhibition gallery guide]. London: Fashion & Textile Museum.

Fashion & Textile Museum (2025) Textiles: The Art of Mankind [Exhibition display label]. London: Fashion & Textile Museum.

Hill, C., Mears, P., Marshall, S. and Steele, V. 2021. Reinvention & restlessness: fashion in the nineties. New York, NY: Rizzoli Electa.

Larsen, J.L. and Hanson, B. (eds). 1976. The Dyer’s Art: Ikat, Batik, Plangi. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Brown, S. and Vacca, F. 2022. Cultural sustainability in fashion: reflections on craft and sustainable development models. Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy. 18(1), pp.590–600.